Editorial

The urban landscape is a kaleidoscope of interconnected elements that come together to form vibrant tapestries of city life. Drawing inspiration from its captivating imagery, “Urban Kaleidoscope” by People’s Resource Centre is a quarterly journal supporting shifting perspectives on cities. By amplifying the voices of citizens, scholars, activist researchers, artists, academicians, professionals, and various community stakeholders, this journal strives to foster critical discourse and cultivate a collective space for the generation of ideas aimed at democratic, sustainable, and inclusive cities.

Through the collaboration of these diverse perspectives, “Urban Kaleidoscope” embarks on a journey of exploration and analysis, shedding light on the complex dynamics of urban existence. More than a platform for alternative visions, policies, and theories, this newsletter catalyzes knowledge creation and resource development for local communities and urban social movements. It aspires to empower individuals and groups, providing them with the tools and information needed to effect necessary change. The editorial collective is committed to building this journal as a unique, democratic, academic intellectual space that can address the anxieties of our times in a language that speaks directly to those whom the current relations of power leave frustrated on an everyday basis and who share a common interest of recovering the city as a place of enriched communal life in balance with nature.

“The city” embodies a certain mythology of “development”, “Growth” and “Freedom” which is experienced in different ways by different groups and communities who find themselves in a complex web of inter-dependence in the city. Queer and Trans folks too experience the city in their subjective ways informed by their social positions and the way their positionality interacts with their queerness. The city for many of us becomes a space for relative anonymity and distance from the structures that govern and police us. What happens when such bodies make it to the city? What are the ways in which they organise themselves? How do they make space in structures that refuse to see them? Is there a possibility of life and flourishing in the city? What are the obstacles to this possibility? There is no one way that queer-trans bodies experience the city, However, these are some questions that we’re interested in exploring through this edition. Queer life and expression in a city is often invisiblised in the way that it is designed and how it reproduces itself. This edition aims to explore the various ways in which Queer and Trans bodies experience and embody the city.

Despite the conception of urban as havens of progress and liberation, especially for queer and trans communities seeking refuge from the constraints of conservative or rural settings, the complex realities faced by LGBTQ+ individuals navigating city life realities are shaped by both opportunity and exclusion. For many queer and trans people cities offer anonymity, cultural vibrancy, and access to affirming communities. However, these same spaces often harbour systemic inequities. Urban planning frequently neglects LGBTQ+ needs, resulting in environments that can feel unsafe or alienating. Public infrastructure such as restrooms, transit systems, and parks rarely reflect the diversity of its users, reinforcing heteronormative and cisnormativity assumptions. Moreover, gentrification and rising housing costs disproportionately impact queer and trans individuals, particularly those from marginalized racial, caste or socioeconomic backgrounds. And displacement of LGBTQ+ communities from historically queer neighbourhoods erodes vital support networks and cultural legacies.

The digital landscape has emerged as both a lifeline and a battleground for queer and trans individuals. Online platforms provide avenues for self-expression, community building, and access to resources, especially critical for those in isolating or hostile physical environments. Notably, a study (Based in America) by Hope lab and the Born This Way Foundation found that 82% of LGBTQ+ youth are out online, compared to 53% in person, highlighting the relative safety and support found in digital spaces. These numbers could be worse if not same for the South Asian or the global south context.

However, these spaces are not without peril. A 2025 GLAAD report indicates a troubling decline in LGBTQ+ safety on major social media platforms, citing weakened hate speech policies and increased online harassment. Such policy lapse is felt more intensely in the global south region, considering a lot of the languages spoken vernacularly are not taken into account for hate speech online by these platforms. Transgender and gender-diverse individuals, in particular, face heightened risks of doxing, blackmail, and networked harassment. We are also witnessing a targeted attack on the transgender community globally, be it Donald Trump or the recent UK Supreme Court judgement. What is common among these is that previously progressive-seeming countries have taken a regressive turn with targeted hate towards the transgender community. The commercialization of queer identities further complicates digital engagement, often prioritizing profit over genuine representation and safety. Pinkwashing is another way that big corporations are able to mask as progressive to expand their consumer markets, outreach and brand Public Relations.

Universities and colleges can serve as critical spaces for identity exploration and community formation. We have a couple of pieces in this edition that explore universities and their own queer bodies as sights of contestation. Some institutions have made strides in inclusivity through gender-neutral facilities and supportive policies. Yet, many still fall short, leaving queer and trans students to navigate environments that may not fully acknowledge or support their identities. The presence—or absence—of inclusive curricula, mental health resources, and affirming campus cultures significantly impacts student well-being and success.

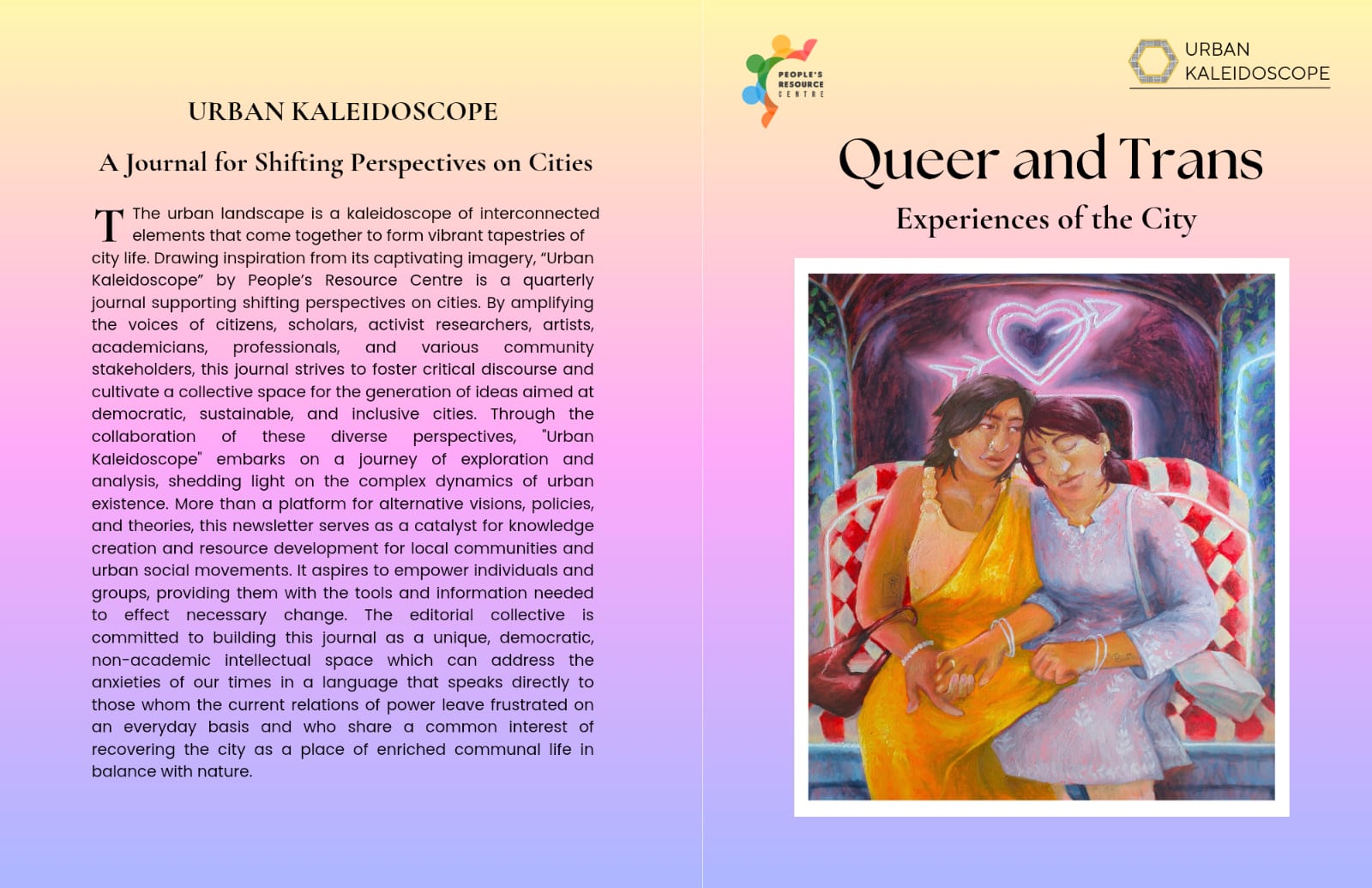

Artistic expression and storytelling are powerful tools for queer and trans communities to assert presence and challenge dominant narratives within urban spaces. In this edition we also have creative submissions like art, poems and stories. Initiatives like “Queering the Map” allow individuals to share personal stories tied to specific locations, effectively queering the geography and highlighting the significance of these spaces in their lives. Such projects not only foster visibility but also serve as acts of resistance and reclamation by the practice of “Counter Mapping”.

We received entries that vary in their medium and content, in this edition we have a selection of pieces that are speaking to our contemporary times and the challenges it poses for thinking about queerness. These pieces range from academic research papers, to personal narratives, poems and artwork. This edition is also bi-lingual and has pieces in English and Hindi. All the pieces in this edition have different pre-occupations and are thinking of queerness from different cities like Hyderabad, Mumbai, Delhi, Pretoria and New York. All of these cities have different socio-historical contexts in which the question of queerness is dealt with in their respective specificity. Some pieces are challenging the construction of “Urban” as a space while some attempt to unpack the idea of “Metronormativity”. Some pieces also look at digital spaces as spaces where unfolding of desires takes place in a certain metropolitan way. Other pieces look at media, personal experiences, university campuses and mobility within the city.

The first two pieces “The Journey of Monalisa: Change of Circumstance and the Travesti Experience of New York” by Antonio Rivera-Montoya and “Metronormativity and the Spatialisation of Queer Desire in Indian Cinema” by Dr. Anandu G looks at media as their primary subject. The first one is about Monalisa and His/Her experience of the city New York in the context of immigration from Chile. Dr. Anandu’s piece analyses the making of a metro-sexuality in Indian cinema, where certain cities like Mumbai and Goa are framed as sights where queerness as an act takes place. In “Digitally Damned: Queer Intimacies in the City” by Dharmesh Chaubey and “Dating Apps And Queer Experience” by Druid, desire is at the centre of city-making as a phenomenon. They elaborate on what and how desire plays out via digital mediations in a city. “‘I don’t know if it’s better elsewhere’: Demystifying dichotomous stereotypes of safety and healthcare among rural and urban black transgender youth in South Africa” by Dr Kudzaiishe Peter Vanyoro questions our assumptions about the “Safe city” and the “Unsafe rural spaces” through case studies from South Africa. Urban is not equal emancipation, safety is not experienced just by urban status, class along with other material conditions inform one’s safety.

In “Trans dreams of a friendly city: Urban Governance and Gender Variant communities in the city” by Krishanu, an attempt is made to understand the complex landscape of urban local governance in Delhi with a focus on inclusion of transgender persons in it. The piece uses a game play and workshop methodology to understand the governance needs of the community. Towards the end it makes a case for Horizontal Reservation for a meaningful representation of the transgender community at all levels of governance structure.

The next two pieces “Towards the ‘Inclusive’ Spaces: A Case Study of Gender-Neutral Spaces at NALSAR University of Law, Hyderabad” by Pallavi Pradhan and “Two Cities, Two Campuses: A Tale” by Gurpartap SinghKaur, explore queerness on Indian university campuses. Both the pieces account for different queer experiences and their interactions with university administrations respectively. Often one of the reasons to migrate to the urban area is education, in this regard university campuses become one of the first sights of navigation for queer folks. Navigation here can mean more than just spatial, it often starts with a reckoning with oneself. Universities too offer a shared space, that helps foster a sense of community which then allows for the possibility of larger queer organising.

Blessy K. Abraham in their piece dive deeper into looking for queer histories in the city through “Hijron Ka Khanqah” a 15th century monument dedicated to transgender community or Hijras situated in Mehrauli, Delhi. In “Male? Female? Or Other?: Experiences of Navigating Transportation as a Transmasculine Person in Delhi”, Shinjini Chatterjee attempts to understand the different ways in which the mobility is experienced by transgender and gender non-conforming individuals.

We have three poem entries from Akhil Katyal that talk of and in terms of the city namely “तुम कोई लोकल स्टेशन होते (If you were a local station)”, “Who Saved You?”, and “Six homes, Six windows”. Another poem “गुलाबी सरहद” (Pink Boundaries) is by Sahej Kisan. One hindi article “शहर में क्यूर-ट्रांस की दुनिया की अलग-अलग कहानी” by Mamta explores a story of two of her childhood best friends and their lives together. Lastly, this edition features artwork titled “I too deserve to love in your city” by Kalaa.

Queerness is not an already formed abstracted category which is found universally. What queerness means is for the queer bodies in their respective contexts to unpack and mediate on. When it comes to queerness in an urban context, it cannot be understood without understanding how capital and caste merge in unison to place different bodies in files of labourers. Neither is desire in the city rid of these infringements of class and caste. What is present in abstraction is hardly found in the way reality is experienced. Cities are also found on a scale of urbanisation. We can no longer continue looking at cities as exclusive sites of urbanisation. Today all cities are on a relative scale of urbanisation, where capital is plunged far and beyond the mega cities. In these cities queerness cannot be seen in a monolithic form, Queer people embody the city as workers, performers, landlords, lovers and more, and urban life then represents an interplay between all these desiring and labouring bodies.

Understanding queer and trans experiences in urban contexts necessitates an intersectional approach. Factors such as race, class, caste, and immigration status intersect with gender and sexual identity, influencing how individuals experience the city. For instance, queer individuals from marginalized racial or socioeconomic backgrounds may face compounded challenges, including limited access to safe housing, employment opportunities, and healthcare. Building cities that are truly inclusive requires intentional efforts to center queer and trans voices in urban planning and policy-making. Global examples illustrate the potential of such approaches. Edinburgh’s feminist urban planning initiatives focus on enhancing safety and inclusivity for marginalized genders, while Chicago’s Boystown neighbourhood features landmarks that honour LGBTQ+ history and culture.

Urban environments hold the potential to be spaces of liberation and belonging for queer and trans individuals. Realizing this potential requires a commitment to inclusivity, equity, and the celebration of diversity in all its forms. By reimagining our cities through queer and trans lenses, we can create urban spaces that not only accommodate but also affirm and uplift all members of our communities.

Rajendra Ravi

Krishanu