Introduction

There has been a larger disengagement from the city’s Urban Governance structure by its dwellers. If we look at this disengagement, why does this disengagement take place? Panchayat-level governance structures are functioning relatively well with public engagement and participation. A lot more people are aware of the office of Sarpanch, but not as many people are aware of the office of Mayor, how they’re elected or what is the function of the office of Mayor in a city.

The question then is what makes it difficult for urban local governance structures to be accessible and used by its citizens. The answer to this question is not a simple or definitive one, for one the problems begin at the governance structure as it is in the status quo. There is little to no awareness about the Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) formed at the city level among its citizens. The culture around public participation in ULBs varies in different cities and states. As it is the prerogative of the State government to implement the 74th Amendment Act, there exists a large variation in the ways it has been realised across different states. Another crucial reason is the weak financial structure of the ULBs. ULBs have a weak taxation power and India’s municipal expenditure is at a depressing one percent of India’s GDP. And with close to no budget, the functioning of ULBs becomes even more difficult. Looking in our context of Delhi, we find that there is an overlap of multiple bodies from Center and State which makes it difficult for ULBs to exercise power.

Another reason as to why engagement by an urban citizen is difficult in the inherent structure is because of how power is placed in a city. City while it is for everyone and signifies a certain aspiration and mobility, does not belong to anyone who makes the city. Cities and in this context, Delhi has a transient and migrant population that is constantly moving. A lot more power in a city is exercised by Capital or big investors, who invest in the vast landscape of infrastructure which constantly keeps the city in the state of “work in progress”. An urban citizen in this context is disenfranchised from the structures that surround them.

For the People’s Resource Center (PRC), the Nagar Swaraj project aims to create and foster engagement with urban local governance structures through public participation. The three-tier federal structure hopes to establish an urban environment that is local in how it functions as it democratises public participation for its citizens at most local levels. We at PRC believe that strengthening public engagement with its Urban Governance structure will result in empowering the different stakeholders in a city. There are various stakeholder engagement meetings done via the UBLs across different states that aim to democratise the functioning of ULBs. Even the prescribed Ward committees have large areas of operation and are not accessible to citizens. We have in our earlier report proposed the concept of “Mohalla Sabhas”, a local-level citizen participatory institution at the booth level. Making Mohalla Sabhas will ensure participation from various communities and social groups who are often erased from the idea of a city. Empowered stakeholders who partake in the daily decision-making of the city enable the democratic functioning of local bodies, which is the aim of the 74th Amendment Act. So it is through our project “Nagar Swaraj” that we aim to engage the different stakeholders in the city to envision themselves in the process of city-making.

This time PRC decided to work with a social group that has been and continues to be marginalised. Gender variant communities are different social groups that do not fit into the binary cis-gender categories. These could be Transgender Persons or Non-binary folks or socio-cultural communities like Hijras and Jogappas. GVC refers to any group of people or communities that do not identify with or fit into the cis-gendered binary framework. With our focus on GVCs, we collaborated with the Naz Foundation to host a workshop with some community members. The idea was to study how GVCs interact with the city and its governance structures. To do this study we used the method of “City Games” an interactive gameplay that allows for participation from the players. This participation is towards the end of making a city together where the city governance structure is Transgender friendly. Players deliberate on different prompts and issues together and try to come to mutually consensual decisions.

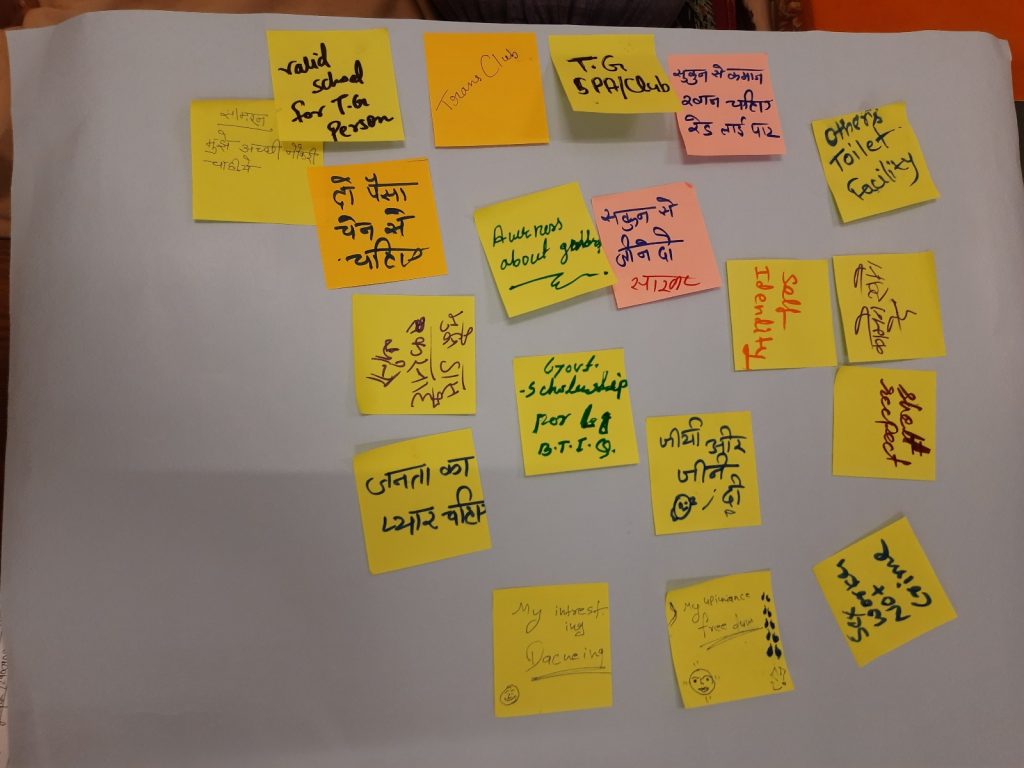

There were several issues shared by the participants, ranging from education, healthcare, and access to public spaces. Some participants also shared how there are almost no public washrooms available for them and that they feel scared while using the binary gender washrooms. They also made demands for a separate washroom in all public spaces. Through the gameplay and sharing around it we gathered insights on how Transgender and Gender Variant Communities do not exist in the imagination of the people who plan and make the city. This results in a city governance infrastructure that is completely unaware of this social group and their needs in the city.

Gender Variant communities in the city

This time for “Nagar Swaraj” we wanted to engage with the idea of “Swaraj” for the gender-variant communities in the city. The aim is to look at how Gender variant communities can imagine themselves in the governance structure of the city. Given that this is a socially and historically marginalised group, their needs and demands for a just city are not included in the way city governance is shaped in the status quo. The key point is “Swaraj” here or self-rule for the transgender community in a city. A good governance structure would be one where the voices of the most marginalised also find representation. One of the first steps to enable this change would be to know and understand the different demands and needs of the stakeholders.

The social world we inhabit is gendered at every step of the way. What that gendering means is that it produces certain precarities for women and men both. However, the gender variant communities or the transgender community find themselves completely out of this structure. First of all, there is a lot of confusion and misinformation about the transgender community. Many confuse transgender persons with intersex persons. Both the communities come under the larger LGBTQIA community but are not the same. Sex can be of three types, typically Male, typically female, and Intersex which can be any combination of both male and female genitalia. Transgender persons are people who are assigned a certain gender at birth say male and then later in life they might not completely identify with that gender and would instead identify as a woman. Transgender persons are also on a spectrum of gender identities, there can be trans-masculine folks, trans-feminine folks and non-binary people, who might not want to relate with either ends of the gender spectrum entirely.

In India, we have many socio-cultural gender variant communities across the country. The Hijra/Kinner community is one of the most visible ones and also exists in Delhi. Against the backdrop of the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871, the trans community was criminalised by the British. Stigma and discrimination have always been the two integral parts of the trans experience. It is because Trans persons are excluded from most of the spaces that they have huddled together in these socio-cultural communities. The ones practicing traditional occupations of “Badhai toli” or begging on street lights, buses, and trains also have to go through daily humiliation and stigma. The Protection of the Rights of Transgender Persons Act was passed by the Union government on August 5th, 2019. While the law claims to protect the rights of transgender persons, many transgender activists find the law to be draconian and claim that it treats transgender persons as second-class citizens.

Given this second context of our stakeholders, it was both a challenging and an enriching task to find out what a Trans friendly city governance looks like. For this task, we decided to collaborate with the Naz Foundation. Naz has a history of working with the LGBTQIA community and that allowed us access to the community members who would talk to us. Since our question was so specific and about the city governance needs of the transgender community, we decided to devise a game. A gameplay would not only allow us to ease into having difficult conversations with the participants it would also be fun and exciting to play! The game also induces the idea of “play” which allows for a fun engagement with each other without the pressure of talking and sharing.

Methodology of “City Games”

The game we devised is called “City Games” and is an attempt at reimagining the city and the city-making process from different stakeholders’ points of view. As a part of the game and depending on the time, materials and other resources one may lay the design of a city on the floor using blocks and other materials signifying buildings, bridges, roads, etc. The game aims to make a city or re-imagine one’s city in a way that facilitates the coexistence of all different stakeholders. All participants are given “role” cards, which describe a certain stakeholder in a city. The Participants are to use the role cards to facilitate conversation and engagement on different conflicts that arise in a city and to come to a mutually agreed upon solution. “Prompts” are introduced to facilitate different discussions among participants, this can be a conflict or a narrative scenario, and can have updates that can be introduced later.

This time we designed the game specifically for the transgender community, where we introduced certain specific “Prompts” that reflect the lived realities of the community. We wanted the participants to engage with the game in a way that we could gain a deeper insight into their lives and the ways that they imagined their existence in the city. There were a total of twenty participants who excitedly participated at all the different stages of the gameplay.

The workshop was held at the Naz Foundation Center, where we met with our hosts and participants. We started by a round of introduction and some sharing on our work and the aim of the workshop. Post which we shared a brief of the gameplay and distributed the materials that were going to be used for the gameplay. We started by dividing the larger cohort into three smaller groups. Considering the time and space we had, we shared a chart paper where participants could draw their vision of the city. We also had one PRC member with each group to facilitate the discussion and to help with any confusion. With this deliberation on city governance structures and the needs of the community began. The facilitator kept introducing different prompts to keep the discussion engaging and relevant. Participants took their time to respond to those prompts in their drawings and writings.

Trans dreams of a friendly city

The participants we had came from similar socio-economic backgrounds where they were a part of community units called “Gharanas” or were from the “Kothi” community and lived independently. Some of them beg at street lights, some do “Badhai Toli” and some also do jobs in BPOs and other corporate places. There were a range of issues that the participants shared, ranging from the need for affordable housing to their right to use public spaces. The context of exclusion of transgender persons from all forms of social life came out as a main cause for these problems. One participant shared “If one has to create a society, then the first thing that is required is a school because without education a society cannot function”. As trans kids grow up they increasingly face violence from different structures around them, including school and natal family. Which often results in them running away or dropping out of school. Schools and universities remain to be places where trans people are not seen as often. Education also becomes an instrumental tool for any community.

Other than this many other demands were shared by the participants. Another participant shared “Every trans person should have a beautiful house, and it should be among society, and no one should discriminate against us and we should be able to live freely as we wish to. Most importantly, the houses should be affordable.”. Housing and affordable, discrimination-free housing was at the core of almost all group discussions as they envisioned a city for themselves. In the status quo, trans persons face a lot of difficulties in securing safe housing for themselves. The real estate prices in a city are beyond the capacity of most working-class trans persons. In such situations, they might turn to rental houses in a city, but many house owners refuse to rent their houses to trans persons, rendering them homeless.

Some participants also shared their concerns about traveling within the city “When we have to travel it becomes difficult to use public transport, the auto drivers and bus drivers do not like to have us as passengers and they also misbehave with us”. This is a general reality with trans persons as they move around the city, a city’s infrastructure is made entirely on the erasure of certain communities and groups, transgender persons being one of them. This concern was elaborated by another participant “If we decide to take the metro for commuting, the binary line for checking becomes an issue, the security personnel stare at us and make us feel uncomfortable, there should be a separate queue for trans persons to enter the metro. And trans people should be hired for the security check.”. The larger public infrastructure is built in a way that it completely excludes the existence of transgender communities. And when a trans person attempts to use this public infrastructure meant for everybody, they are met with violence.

Participants also shared how this is a problem not only of the queues in the metro but also of all public washrooms. All public washrooms have only two sections for men and women. One could say that trans-feminine persons should go to women’s washrooms and trans-masculine folks should go to men’s washrooms. But this solution leaves out the non-binary identifying population. And even if it were to work out for binary transgender persons, it completely misses the point about the inherent violence that is omnipresent on trans bodies in public spaces. Policing of trans bodies takes place almost everywhere, gender however social it might be, it is through these daily realities that it manifests itself. Some participants also shared how a similar kind of discrimination happens to them at hospitals when they are put in wards of the gender they do not identify with. For all of these concerns, making an exclusive, third, or trans queue, washroom and ward at hospitals might help facilitate the movement of trans and gender-diverse bodies in public infrastructure.

Trans persons often do not have a lot of choices when it comes to livelihood, due to stigma and historical marginalisation most trans persons have to choose from a small range of traditional occupations. “Even if we wish to start alternative jobs by ourselves, there are different problems. We often do not have enough funds to start a business and even if we do, none of us have documents required to do the paperwork”. In an ideal city where city governance is imagined as trans-friendly, the city governance must be sensitive to the needs of the trans community when it comes to livelihood. What this looks like can vary from a designated documentation center where trans persons can come to furbish documents for themselves to helping them access social welfare schemes at the municipal level.

For marginalised communities dealing with immediate survival, needs tend to stop at food security, employment, etc. There are other needs of people in a city that the city governance and infrastructure should be responsible for, one such need is leisure. A participant shared “There are many people from our community who might be interested in Sports but they never got the opportunity to play, we need a facility so that we can also enhance our skills and partake in leisure”. It should be upon city governance structures to take cognisance of the varied public needs to be able to build a truly public infrastructure.

Conclusion

One of the participants asserted that “People should know about the Transgender Act”. The Protection of Transgender Persons Act was enacted in 2019 and it brings transgender persons and gender variant persons under the purview of law. Trans persons are recognised citizens and hence are entitled to all the rights guaranteed to the citizens of this country. Urban local bodies and people working in it hardly have any information about the Act or what it says. Many times for them to be heard transgender persons have to enter these offices with a copy of the Act. The Urban local bodies can start by acquainting themselves with the law. One huge task under the Trans Act prescribed under the Urban local body is the issuance of a “Transgender (TG) Card”. Currently, this process takes anywhere between two months to two years depending on the region and the government official one might be dealing with. Because this very process is at the mercy of the public official one has to deal with there is no uniformity in the practice. The Trans Act also mandates reading of it per all other existing Acts and that welfare schemes, syllabi, etc be revised to accommodate trans and gender variant individuals. This is to be done on all levels, but we hardly see any compliance with the law unless pushed by local activists.

We started by trying to understand why the engagement for urban local bodies was so low, we charted out the structural problems and then some other issues one might encounter. We’ve seen how with any stakeholder, engagement becomes difficult, and what these difficulties look like change with their varied social locations. With a trans-person the struggles are varied, firstly there is a larger initialisation that the community deals with. Erasure not only from the registers of governmentality but from all forms of organised social life like family. This leads to a life lived under stigma, where misinformation replaces the lack of any information about trans persons and their bodies. Such an erasure and stigma along with misinformation results in various forms of violence that trans persons go through daily. Issues faced by trans folks are social in the way that their identity excludes them from what is imagined as “normal”. And this exclusion is reflected in the way city planners and administrators imagine and shape the city. Which then in turn affects the material conditions of trans persons. Far away from a friendly public infrastructure that enables free movement and interaction between bodies, there is no public infrastructure for trans folks to exist in. For Trans persons to exist meaningfully in a city ecosystem need material and non-material things like Education, employment, dignity, and leisure.

If we look at the kind of needs that have come out of this workshop, we can notice the focus on public infrastructure that can only be given by the state. Having these resources and materials, the community can advocate for themselves in the society as they’d then become an equal stakeholder with the others. All trans persons shall benefit from public welfare schemes and a public infrastructure truly made for all. In this regard, we can understand how trans issues are also issues of class and caste.

Report by Krishanu, Research Assistant

Note: Images in the article have been edited through A.I. to maintain the confidentiality of the workshop participants.

Key Terms:

- Cis-gender – People who identify with the sex assigned to them at birth.

- Transgender – People who do not identify with the sex assigned at birth and determine their own gender identity. There can be two broad distinctions under the Trnasgeder identity, trans-masculine and trans-feminie.

- Non-binary – People who do not identify with the sex assigned to them at birth and also do not abide by the binary genders of masculinity and femininity. This, too, is a broad spectrum where Non-binary folks can have their own articulations of gender identity and varied expression.

- Hijra- This is one socio-cultural-historic community of transgender persons in the South Asian context. Hijras are trans-feminine folks who organise themselves in traditional “Gharanas” and perform traditional occupations.

- Jogappas – A community of transgender persons from North of Karnataka