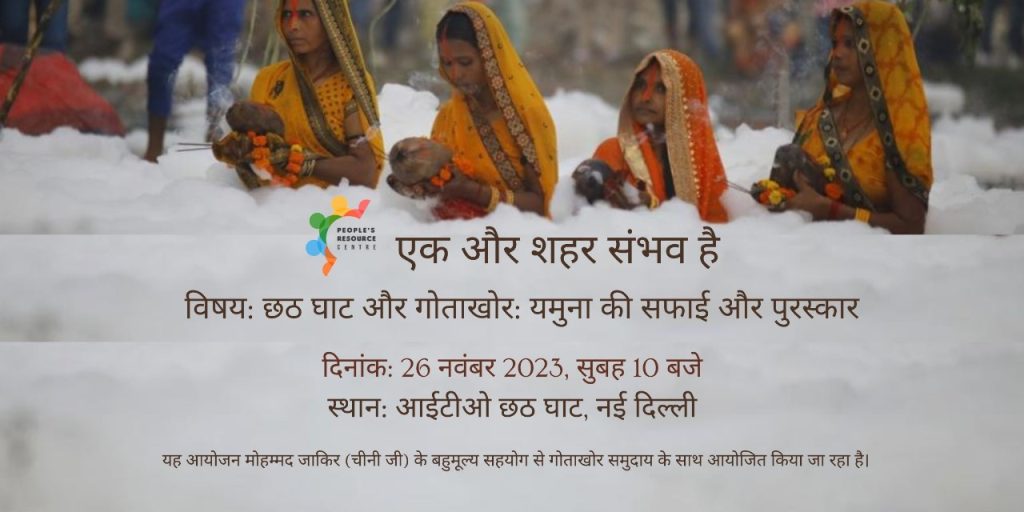

The Yamuna ghats were smogged, cleaned, and re-constructed during the Chatth Puja. Fasting women went into the toxic and foamy water flowing into the Yamuna to worship the sun god. Politicians across the spectrum took up the task of developing the Chatth Ghat at the banks of Yamuna for Purvanchalis, a significant chunk of the voters in Delhi. Amidst this, the politicians and devotees overlook the people living near and surviving off the Yamuna. These people come from various backgrounds, including rag-pickers, gotakhors, fisher communities, washermen, agriculturalists, etc. The cleanliness efforts seem to be a one-off thing annually, whereas communities like Gotakhors clean the ghats of Yamuna throughout the year without any incentives. The mere incentive is the finds from Yamuna or money they charge to deep puja material into the river.

This episode of Another City is Possible recapitulates the critical role of the local communities in the river’s ecosystem. The Gotakhors are a community that has contributed significantly to keeping the river and the ghat clean. They are honed in diving and swimming skills, and they keep the water clean by retrieving and removing numerous objects from the river and even assisting in disasters or accidents. This episode aspires to highlight the essential role played by such local communities in maintaining the cleanliness of Yamuna and formulate the vision of another city where these communities are better positioned in the current socio-economic and political system and whose efforts are duly acknowledged and revered.

Yamuna’s Pollution

Yamuna is uniquely situated on the margins of Delhi, unlike other rivers that crisscross the cities, for instance, the Thames in London or the Ganga in Patna. Cities in Delhi, such as Shahjahanabad, came up on the Western banks of Yamuna since the Eastern bank was swampy and uninhabitable. The British unconventionally thwarted this practice and started building near the Aravali ridge.

The origin of Yamuna is traced from the white mountains of the Himalayas, making its way through the Shivaliks and taking a detour on the terai region of Haryana before entering Delhi, near the Palla village. The part of Yamuna before Haryana is clean and pristine. But as it enters Haryana and Delhi, the water of Yamuna is immensely murky and putrefied.

Historically, Yamuna has been the lifeline of Delhi due to its potable water, which used to be stored in several tanks and hauzs including, for instance, the Hauz-i-Shamsi for drinking purposes. It was not until the mid-nineteenth century that the Yamuna’s water became unfit for drinking.

Over the years, several tributaries and nallas travelling from Rajasthan bringing their foul water to the Yamuna, such as the Najafgarh nala, led to its contamination—in addition to the seepage of the domestic and industrial wastewater generated from East Delhi, Noida and Sahibabad into Yamuna.

Gotakhors Role in Yamuna Cleaning in Their Voice:

One of the Gotakhors recalls his journey from the tender age of eight; he embraced the river as his home and lifeline and learned the lifestyle and courage from uncles and elders. As they plunged into its depths, they inherited a legacy, their bodies becoming adept at navigating the flow as passed down through generations of being the first responders answering the river’s call. One of them pointed out far across the ghat, their homes built on one end. However, their work domain has extended to encompass the entire riverbank, yielding a sense of familiarity forged through years of immersion in the river’s rhythm.

Yet, amidst the crowds that flocked to the ghats, eager to celebrate or offer prayers, the Gotakhors often remained unnoticed, their quiet dedication drowned out by the masses. These visitors often carelessly step across the lines and appear as intruders, as expressed by the Gotakhors who participated in the conversation.

Experiencing ‘Festivals’ and Interacting with ‘Outsiders’:

Living in a close-knit community, they share their knowledge, skills, work hours and responsibilities. Understandably, a sense of shared gratitude has developed in the hearts of these divers dependent on the river on their worst days. Yet, amidst these feelings of belongingness, a shadow lingers. Outsiders, disguised as well-meaning NGO workers and political leaders, enter their world with promises echoing like tempting melodies. They vow to cleanse the river and uplift the Gotakhors’ livelihoods, painting a future of prosperity. But the Gotakhors, wiser with experience, have learned to discern between hollow words and genuine intent. Amidst the clash between claims and reality, the narrative surrounding the Yamuna ghats has been in control of those seeking publicity and power.

Well-funded NGOs, with resources far exceeding those of the Gotakhors, skillfully manipulate the public perception of the ghats, exaggerating the role of social workers while minimising the contributions of the Gotakhors. The reality, however, is far removed from this fabricated facade. In rare instances, a semblance of collaboration emerges between these social workers and the Gotakhors, but organisations are well-versed in exploiting the marginalised and consistently perpetuating the same narrative.

The Gotakhors, desperate for recognition and support, offer their time, energy, and meagre resources to these organisations, who, in turn, stage minimal cleanup efforts, just enough to capture impactful images for public consumption. A substantial source of income for the Gotakhors comes through the rituals performed at the ghats, either at festivals or otherwise. The NGOs, ever eager for a photo op, descend upon the scene, capturing images and political leaders, too, make their appearance with hollow words that vanish as quickly as they arrive.

Amidst the festivities of Chhat, particularly, the ghats transform into a makeshift stage, their garbage concealed beneath carpets and tents. Food, a luxury beyond the Gotakhors’ reach, is lavishly served. Registration desks sprout like mushrooms, each accepting hundreds from every participating family. The Chhath festival, with its strict prohibition on visarjan, further disrupts the Gotakhors’ rhythm, hindering their work and depleting their income.

Following the festivities, the ghats are cleaned, not by the Gotakhors, but by the Chhath Samiti, a committee entrusted with the task. The Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD), the Public Works Department (PWD), and other organisations play their part. The Delhi Development Authority (DDA), a recent addition to the cast, oversees the cleaning and maintenance.

As the crowds disperse and the festive atmosphere dissipates, the Gotakhors return to their familiar routine, and the ghats, once again, become their sanctuary, their livelihood, their very existence. Their experiences with these outsiders have left deep scars as they repeatedly witnessed unfulfilled promises, token compensations, and blatant disregard for their expertise and contributions. Their trust in the state has dwindled and been replaced by anxiety for their future as caretakers of the river.

Conclusion :

Discussion with the Gotakhors’ reveals their life as a tapestry woven with hardship and resilience. Meagre compensation, dwindling financial resources, and a gnawing absence of recognition paint a bleak picture of their existence. Their rights as citizens are severely compromised, without registered licences and even identity cards. Their predecessors once held these documents, granting them a monthly stipend and a sense of dignity. However, these privileges have long vanished, leaving the Gotakhors to navigate a government maze of bribery, shifting blame, and endless rounds from one office to another.

For many, payment for their services comes in the form of in-kind goods rather than cash. In fact, the connections they forge by rescuing lives from the Yamuna’s depths provide them with their true identity, a lifeline in a world that often seems to have forgotten them.

In the face of these challenges, the Gotakhors find solace in their unwavering belief in the Yamuna’s grace. Their faith in the Yamuna is their anchor, their source of strength amidst the relentless tides of adversity.

“Sab Yamuna ki kripa se chal raha hai,”

“Jab koi kuch nahi deta, nadi hi kabhi kabhi seedha sona deti hai. Hum toh Yamuna ke bharose hain, hamara khayal rakhti hain.”

Report prepared by Sidhant Kumar (Research Assistant) and Vibhuthi (Intern)