Cities, Democracy, and the Question of Rights to Community Resources

Event Report | 27 August 2025

Organized by PARISAR, People’s Resource Centre (PRC), and Institute for Democracy and Sustainability (IDS)

The concept of ‘development’ as it is being presented in metropolises like Delhi today is limited to the construction of infrastructure only – projects with wide roads, flyovers, multi-storey parking, and cosmetic “green washing”. But the important question is who is benefiting from this development and who is being marginalized.

The National Environmental Policy (NEP) and India’s National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) talk of ‘local participation’, ‘community engagement’ and ‘green growth’. In contrast, building fancy riverfronts, fences, and event spaces along the Yamuna is in direct contradiction to the basic objectives of these policies. Converting a living ecosystem into a performance platform is not only against environmental justice but also a violation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG-11 (Sustainable Cities).

Today, when entry fees have been imposed in city parks, it clearly shows that public resources are no longer for the common people. The urban poor, women, queer and trans, migrant workers, small vendors and farming communities—all are paying the ‘price’ of this so-called development.

Cities are now giving way to ‘beautiful places for the rich’, replacing the poor. This is not only increasing spatial inequality, but also shattering the concept of social justice.

To address and discuss all these issues on 27th August 2025, PARISAR, in collaboration with People’s Resource Centre (PRC) and Institute for Democracy and Sustainability (IDS), hosted a day-long public event titled “Cities, Democracy, and the Question of Rights to Community Resources”. The programme focused on intersecting themes of urban transformation, river ecologies, community rights, gender justice, and the lived realities of queer and trans communities in Indian cities.

This inclusive gathering brought together a diverse group of participants including environmentalists, urban practitioners, students, community members, and activists to share critical reflections and lived experiences around questions of city-making, river conservation, and identity-based exclusions in urban spaces.

Programme Outline

1:30 PM – Exhibition Opening

Theme: Sahibi River – A Journey Towards Extinction

Inauguration by: Sohail Hashmi, historian and heritage activist

2:00 PM – 4:00 PM – Report Launches & Panel Discussion

Theme: City, Conservation of River and Community Resources and Community Rights

High Tea Break

Evening Session

4:15 PM – 6:00 PM – Urban Kaleidoscope Journal Launch and Panel Discussion

Theme: Queer and Trans: Experiences of the City

6:00 PM – 7:00 PM – Drag Performance by Avtari Devi

Performance Title: Dil, Dilli, Dehleez

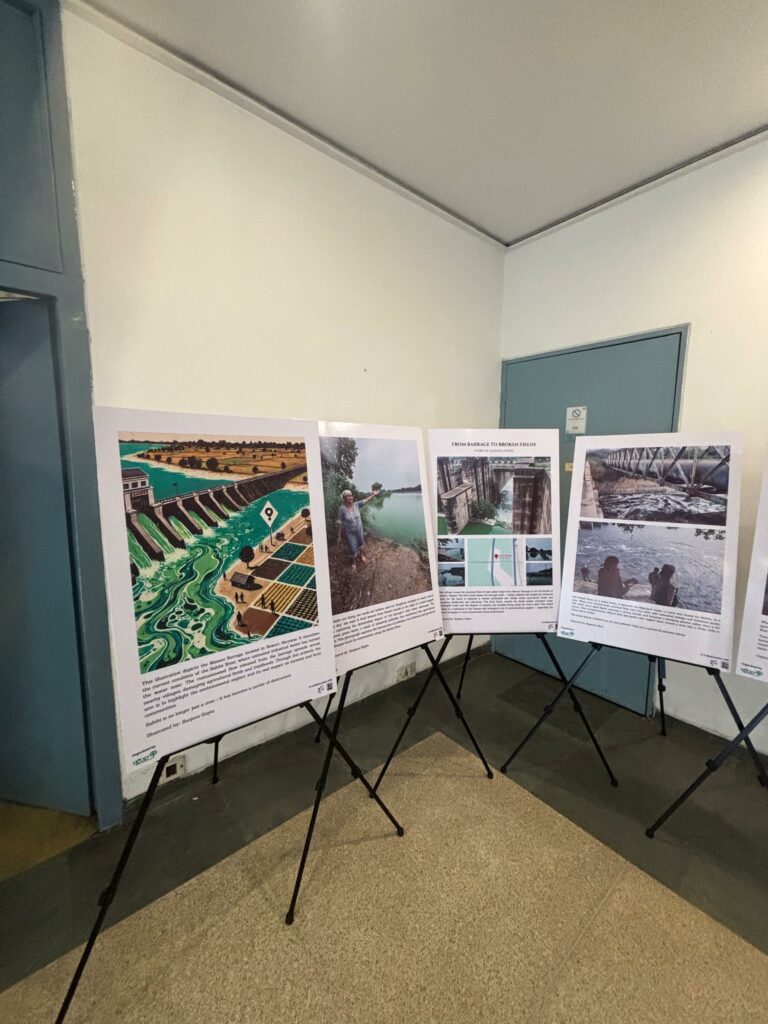

Exhibition on the Sahibi River

The day began with the inauguration of an evocative exhibition on the Sahibi River by Sohail Hashmi, renowned historian and heritage conservationist who reflected on the historical relationship between Delhi and its rivers, especially the Yamuna. He contextualized the Sahibi’s transformation from a vital water body to the Najafgarh Drain and its implications for Delhi’s ecology and communities. Sahibi originates in the Aravalli hills in Rajasthan, beginning its journey from the Pithampur and Bari Jodi region and winding through Jaipur, Alwar, and Gurgaon in Haryana before crossing into the National Capital Territory of Delhi via Dhansa border.

Sohail Hashmi mentioned during his inaugural address that “Sahibi is a small tributary of the Yamuna river, and there are various 16 small tributaries like Sahibi, which have turned into dirty drain which are carrying the filth and merges with the yamuna and water of the river gets polluted. So if Yamuna has to be cleaned then these small drains will have to be cleaned first.”

Once it enters Delhi, the river is more commonly referred to as the Najafgarh drain, a name that reflects its present state more than its historical identity. Eventually, the Sahibi merges with the Yamuna River at Wazirabad, and from there, its waters make their way into the Ganga at Allahabad. Over the decades, the river has increasingly become an example of how urban expansion, infrastructural interventions, and bureaucratic oversight can drive a natural water body toward extinction.

This exhibition unfolds in four sections, each offering a glimpse into the layered story of the Sahibi River, a river now largely reduced to a drain, yet central to the daily reproduction of the city.

Section One explores how the river is visually constructed in public messaging. Using digital art and photo manipulation, the artist juxtaposes Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) wall murals and Public Service Announcements with photographs of the river’s current condition. These contrasting images highlight the disconnect between official portrayals and lived realities. Section Two documents the life that still clings to the river’s edges—plants, birds, and animals that survive despite the pollution. This section asks us to reconsider what kinds of ecosystems emerge and endure even in degraded environments. Section Three presents stark imagery of construction and urban development crowding the riverbanks. These visuals underscore how infrastructure projects, landfills, and concrete embankments reshape the landscape, often to the detriment of the river’s natural flow and ecology. Section Four invites viewers to pause. It features quiet, contemplative stills of the river—a river that once flowed with life.

The exhibit interrogated dominant ideas of “development”—highlighting how infrastructure-led urban growth often marginalizes vulnerable communities and erodes public ecological commons. The presentations invoked constitutional guarantees (Articles 14, 21, 39(b)) to remind participants of the rights to equality, dignity, and shared resources, often undermined by unchecked urban interventions in the name of development.

Report Launch & Panel Discussion : City, River, and Community Rights and Community Resources

Since ancient times, cities have flourished along rivers. If we look at Indian cities, most are situated on riverbanks, Delhi on the Yamuna, Patna on the Ganga, Ahmedabad on the Sabarmati, Agra on the Yamuna, and Hyderabad on the Musi River, among others. There were compelling reasons for settling near rivers; they provided essential resources for survival, including water, food, transportation, and irrigation. Beyond their practical utility, rivers have served as cultural and ecological lifelines, becoming inseparable from a city’s identity.

However, over time, this bond has weakened. Rapid and unplanned urbanization has distanced cities from their rivers. Encroachment, pollution, infrastructure projects, and neglect have severely damaged river ecosystems. This degradation has not only disrupted ecological balance but also altered the deep connection between humans and rivers, threatening the very existence of these water bodies.

Delhi is a stark example. While the Yamuna’s pollution is debated annually, its tributaries are ignored and not even talked about. Superficial solutions, like dredging silt or constructing riverfronts, are prioritized, displacing long-standing communities while failing to address the root causes of pollution. The real sources of contamination, industrial waste, untreated sewage, and commercial effluents, continue to flow unchecked into the Yamuna through its tributaries and drains.

Our team has conducted a study on the Sahibi River, examining the broader challenges of urbanization, encroachment on shared resources, and river conservation. While cities modernize, the destruction of common resources like the Sahibi continues unchecked. Understanding the river’s history and ecological role is crucial for preserving Delhi’s environmental and cultural heritage, a subject now gaining scholarly attention.

Across India, including Delhi, the Sabarmati Riverfront model is often cited for river restoration. However, these projects prioritize cosmetic beautification over addressing core issues like pollution and displacement. In the name of “development” river-dependent communities, fisherfolk, informal labourers, local residents, and small businesses are evicted, severing their centuries-old connection with these water bodies. True river revival requires community participation, ecological restoration, and cultural preservation, not just superficial makeovers that exclude the very people who depend on these ecosystems.

A panel discussion organized on all these issues, in which various aspects of the coexistence of cities and rivers will be discussed. In particular, this conversation examined the historical, social, and ecological relationships between cities and rivers, as well as the processes of state management, control, and reconstruction. This panel discussion engaged in a serious dialogue on the journey from the destruction to the revival of rivers, and the changing nature of the relationships between the state, communities, and the environment throughout this process. Researchers, academicians, social workers, and activists working on environmental issues were speakers in this discussion, shared their experiences and work with the audience. Report launch on the Sahibi river was followed by the panel discussion.

This session opened with the launch of two significant publications:

- “Sahibi: A River Promised”

- “Urban Water Bodies in Delhi”

Moderator: Soumya Dutta, Environmentalist

Panelists:

- Dr. Ivy Dhar (Ambedkar University, Delhi): Provided a critical analysis of governance models and river-centric urban planning policies, with a focus on informal settlements and rights-based approaches.

- Dr. Ritu Rao (River conservation practitioner): Presented a visual and historical account of the Sahibi River, tracing its journey from origin to its confluence with the Yamuna.

- Krishnakant (Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti, Gujarat): Shared insights on riverfront development projects in Gujarat, especially the Tapi River in Surat, drawing attention to patterns of ecological erasure across states.

- Neha Sarwate (Architect and Environmental Planner, Baroda): Discussed the environmental threats and development pressures facing the Vishwamitri River in Gujarat.

Dr. Rajendra Ravi welcomed all panel members and talked about the work People’s Resource Center is doing for the last three decades in Delhi on various issues including conservation of Rivers. Dr. Ravi talked about the early days when he came to Delhi and saw the situation of Rickshaw pullers. He also talked about dislocation of people living along the banks of Yamuna River in Delhi alleging they were polluting the river but the river is now even more polluted even after the people are dislocated.

A brief from the panelists:

Dr. Ivy Dhar from Ambedkar University opened the panel discussion by highlighting the issues faced by residents of unauthorized colonies in Delhi, which lack sewage systems and proper drinking water supply. These colonies, developed on former agricultural land sold by farmers after legal changes, were allowed to grow despite lacking official authorization. Dr. Dhar emphasized that the government must provide basic services like drainage and clean water to prevent pollution from untreated human waste flowing into open drains.

Dr. Ritu Rao, a river conservation activist, discussed the nature of rivers and the efforts by civil society to revive them through initiatives like River Front Development. She focused on the Sahibi River, a seasonal rain-fed river originating in Jaipur, which historically helped prevent floods and supported irrigation through barrages. However, one such barrage in Rewari, Haryana, is now filled with sewage from Rewari and Manesar, leading to overflow and pollution of nearby farmlands. This has caused crop and soil damage, prompting farmers to raise concerns. Activist and journalist Prakash Yadav brought the issue to the National Green Tribunal (NGT), which ordered authorities to treat the sewage and revive the river. Dr. Rao noted that despite the NGT’s directive, effective implementation remains challenging without active involvement from affected communities.

Krishnakant, Social Activist talked about how the rivers are being corporatized by construction of river fronts, its beautification and attracting people to visit these places for walk by paying a fee for entry. Rainwater is not being directed towards rivers because the roads being constructed do not have proper drainage connected to rivers. There are reports available to show how and why this is happening, who is being benefited and who is suffering due to bad infrastructure inviting disaster.

Krishnakant observed that the people have to come together and protest against the development of bad infrastructure benefitting corporates and poor people are paying a price by way of diseases spreading due to pollution.

Neha Sarwate, architect and environment planner, spoke about the deteriorating condition of the Sahibi River, now visible only in a few places. She emphasized that its revival requires coordinated action by Rajasthan, Haryana, and Delhi. After the 1977 floods, the Masani Barrage in Rewari was built, but it now carries sewage from nearby towns instead of clean river water. Once a key source of irrigation, the polluted river water has made many crops unviable, forcing farmers to rely on tubewells. This shift is rapidly depleting groundwater levels, worsening the crisis.

Audience Questions and Panel Responses:

Q1: How can we clean the Sahibi River?

Neha Sarwate explained that while the National Green Tribunal (NGT) has issued directives for cleaning and reviving the Sahibi River, implementing these orders is a complex challenge. Bureaucratic systems often interpret such orders in ways that delay or dilute their execution. Real change, she emphasized, depends on sustained pressure from civil society and activists who must engage persistently with the authorities. For meaningful results, the issue must transform into a people’s movement where communities actively demand action and accountability.

Q2: Can river conservation become a political issue, and should it be raised during elections?

Panelists agreed that water and river issues should be treated as core community concerns—just like housing, health, or education—and raised as demands during elections. The public must collectively voice these concerns at political forums to push parties to take responsibility.

Saumya Dutta shared a powerful example from a small town in West Bengal, where residents united to demand the revival of a dying river. Their sustained activism turned into a local movement, compelling the government to act. The river, once almost vanished, is now flowing again demonstrating that collective action can bring about real change.

The discussion explored the complex intersections between ecological destruction, governance, and community displacement. It unpacked how cities relate to rivers historically, socially, and ecologically questioning the role of the state and the growing influence of privatized urbanism in reshaping public resources.

The session saw enthusiastic participation from a wide spectrum of attendees, including students from Savitribai Phule Community Centre (Bawana), university students, labour union members, social workers, and academics adding to the richness and diversity of the dialogue.

Urban Kaleidoscope Journal Launch

The post-tea session commenced with the launch of the fifth edition of Urban Kaleidoscope, Urban Kaleidoscope, a quarterly journal by People’s Resource Centre, serves as a collaborative platform where scholars, artists, activists, researchers, and community members share critical reflections on urban life. With a commitment to democratic, inclusive, and sustainable cities, the journal amplifies diverse voices to explore how different communities experience urban spaces, especially those historically excluded from mainstream planning and discourse. This edition focuses on queer and trans experiences in cities, unpacking how these identities intersect with urban structures, policies, and everyday life.

This edition, titled “Queer and Trans: Experiences of the City”, delves into how queerness is both expressed and constrained by urban life. It asks vital questions: How do queer and trans bodies claim space in cities that structurally ignore them? Is there room for flourishing within systems that often deny recognition and safety? The journal approaches these questions by featuring a range of content, academic essays, personal narratives, poetry, artwork, and bilingual contributions in English and Hindi, spanning cities such as Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Pretoria, and New York.

The edition rejects monolithic understandings of queerness. Instead, it situates queer and trans experiences within broader systems of caste, class, and capital. Urban life is shown not merely as a backdrop but as an active site where desires, labour, and identities are constantly negotiated. The contributors argue that queerness is not a universal abstraction but something rooted in context, shaped by structural realities and lived struggles.

Panel Discussion: Queer and Trans Experiences of the City

Moderator: Krishanu, Research Associate, PRC

Panelists:

- Ritu Rao, Trans Activist, NAPM

- Zayan (he/him), Dalit Queer Feminist, YP Foundation

- Nu (They/He), Founder, Revival Disability India

- Dhrubo Jyoti, Journalist and Writer

(Pavel Sagolsem was unable to attend; Ritu Rao graciously stepped in)

Nu, Founder – Revival Disability India mentioned that “Not every body is fit for the city infrastructure, city also discriminates people on the basis of their disability and gender and city creates divide on the basis of their gender, caste, class and race”

The panel discussed how queerness is negotiated in city spaces shaped by casteism, cis-heteronormativity, and class structures. Cities are often portrayed as emancipatory spaces, yet access to safety, visibility, and housing remains elusive for many queer and trans individuals particularly those from Dalit, working-class, or disabled backgrounds. Ritu Rao, one of the panelists mentioned that “Queer people are also engaged and fighting for the general rights of the citizens, they are also disturbed due to the pressure of capitalism and increased financial burdens just like any other citizen of the country so if everybody will start engaging and raising everybody else rights then to gain rights in the society would be very easy and person with any identity would be able to live together.”

There were some concerns raised about the queer rights not being delivered by the society or the government expressed by the panellists but the concerns were not limited to queer community only and are being faced by every citizen of the country.

In conclusion, Urban Kaleidoscope challenges us to rethink cities not as neutral spaces, but as contested terrains where inclusion must be intentionally designed. By centering queer and trans voices, especially those further marginalized by caste, race, or class, we can envision cities that affirm diversity and justice. Through layered storytelling, critical analysis, and creative resistance, this edition invites us to reimagine the urban as a space of possibility, one where all bodies can belong, thrive, and reshape the city on their own terms.

Closing Session

Drag Performance: Dil, Dilli, Dehleez by Avtari Devi

The evening culminated with a powerful drag performance by Avtari Devi, works at reimagining Launda Naach- a folk-theatre form from Bihar where men, boys and all kinds of trans locations dress as women. Avatari hails from Buxar, Bihar, the same where battles have been fought and they inherit some of that feistiness well. Their everyday avatar, Swaja Saransh is an award-winning filmmaker and performance artist based in Delhi. They have performed at Rainbow Literature Festival, Shoonya, Gender Bender Festival, Do Din at Hyderabad Urban Lab and most recently, conceptualised and executed the first iteration of Dehleez in Edinburgh, UK.

About the performance – Dil, Dilli, Dehleez, ‘Dehleez, chaukhat, threshold- a word that separates us from the world, the private from the public, civility from uncivility and freedom from nuisance? Avatari explores its many meanings in this performance, testing the dehleez of our current context and cities that anyway do not like to stay within those limits, Do they? Come and ye shall know.’

The main intention behind including this performance was to provide a powerful visual and emotional lens into the lived realities of someone navigating a new city grappling with its unfamiliar rhythms, social codes, and invisible thresholds. To have an interactive session between the performer and audience. At the same time, it served as a vital moment of visibility for queer performance and expression, bringing to the forefront an art form that has long existed on the margins. Through Avtari Devi’s performance, the audience was invited to witness not just the story of adaptation and survival in the city, but also the bold reclamation of identity and space by someone who exists outside the heteronormative framework. In showcasing drag and reimagining folk traditions like Launda Naach, the performance challenged dominant cultural narratives and celebrated the creative agency of queer artists. It was an act of resistance and affirmation, reminding the audience of the importance of embracing diverse identities and of recognizing queer and trans art not as peripheral, but as integral to the cultural and political fabric of our cities.

Conclusion

The event “Cities, Democracy and the Question of Rights to Community Resources” succeeded in creating a multi-dimensional dialogue between ecology, gender, urban planning, and democratic rights. It challenged dominant development narratives and foregrounded the voices of those living at the margins of both city and discourse.

By fostering connections between rivers and rights, queerness and urban belonging, the day offered a powerful reimagining of the city—not as a space of exclusion, but of possibility and collective action.

Amidst growing urban challenges, the People’s Resource Centre (PRC) has been actively working for several years on promoting an alternative and inclusive vision of urbanization. PRC envisions a city where every citizen enjoys equal rights and where democratic participation extends beyond voting to include active involvement from all sections of society in city planning, resource allocation, and infrastructure development. At the heart of PRC’s urban model is the belief that clean air, clean water, and nutritious food are fundamental rights. It emphasizes the importance of ensuring the local production and equitable distribution of fresh, healthy food, while also promoting community gardening and urban farming in place of wasteful land use like garbage dumps. PRC advocates for rivers and green spaces to serve as public, cultural, and social commons, fostering community interaction and environmental restoration. Crucially, it challenges the commodification of resources, instead promoting collective ownership and shared responsibility. Cities like Delhi, PRC argues, should not be designed merely for concrete structures and vehicles, but as inclusive spaces that nurture life, relationships, ecology, and democracy. Excluding ordinary citizens from current development models not only leads to social and environmental degradation but also undermines the values enshrined in the Constitution. To address this, we must strive for a model of urbanization that is constitutional, ecologically sustainable, and socially just—an approach that PRC continues to inspire through its initiatives.