Wild sea waves

weather the coastlines,

while wind in deserts

carve mushroom rocks.

Rain and frost

weather the earth,

like glaciers and snow

in temperate zones.

But the sculpting “effect of running water

is felt all over the globe”

Perhaps the gradients of earth have given significant activities to rivers. The most important tasks of erosion, transportation and deposition. Just a simple flow of running water reducing the earth to beautiful landforms such as gorges, waterfalls, floodplains, or deltas.

However, it is quite a complex flow. During the stage of youth (1), rivers are voracious and swift and cuts through the mountains vertically forming valleys, waterfalls or rapids. They are fearful and intimidating then. And when they are old, they bring large quantities of sediments helpful for agriculture expanding laterally forming extensive floodplains before vanishing into the sea or forming beautiful lakes or swamps.

Who is a river?

When we speak of rivers, are we really speaking of all rivers? Or are our minds captured by just a few—those famously wild, ferocious ones cutting through the mountains? A conscious reading of what I’ve written above would reveal my own bias (2) imagining rivers as humongous forces, cutting through rock, shaping valleys and gorges.

But such an imagination excludes the quieter ones—rivers that rise in low-lying plains, meander gently, and lack the dramatic currents or spectacular erosional landscapes that dominate popular imagery. This blog interrogates the socio-political and ecological framing of rivers in contemporary India, revealing how symbolic valorisation often coexists with material neglect. It examines how state narratives and policy instruments construct hierarchies among rivers, privileging certain forms of cultural and political significance while relegating others to the margins.

Ganges, Yamuna, Hindon, Sahibi, Gangan—they are all rivers, yes. But are they of the same status? Are they treated the same, remembered the same, valued or loved the same?

Let’s consider the Yamuna and the Hindon. Most people have at least heard of both—though perhaps not the latter. But does that recognition make them equal? I suspect not. The difference lies not in the kilometres they cover or the width they stretch, but in how the state manages them, how people perceive them, and what kinds of stories—myths, memories, religious rituals—cling to their banks.

The Yamuna, like the Ganga, is venerated. Sacred, symbolic, politicised. Even in its filthiest stretch through Delhi, it commands a kind of caution, even reverence.

Now consider the Hindon—a tributary of the Yamuna. Equally polluted, perhaps even more neglected. But it is not venerated like Yamuna. It is forgotten. It is treated as expendable, available, dispensable. Anyone who lives near Char Murti in Greater Noida can see this firsthand—the river reduced to a drainage canal, barely noticed by those who pass it daily.

Figure 1: Hindon River as seen from Char Murti Chowk in Greater Noida. Note how both banks have been surrendered to development—there’s a cricket pitch on the left and an exhibition ground on the right. While taking this photo, I observed three people stop their vehicles to throw something into the river. (Photo credit: Nirjesh)

Figure 1: Hindon River as seen from Char Murti Chowk in Greater Noida. Note how both banks have been surrendered to development—there’s a cricket pitch on the left and an exhibition ground on the right. While taking this photo, I observed three people stop their vehicles to throw something into the river. (Photo credit: Nirjesh)

In lived experience, not every river is just a river. The state assigns them social status—some are personified, even deified—and vast sums are spent in the name of rejuvenation or cleaning, often without addressing the sources of pollution.

The Ministry, too, treats rivers not as ecological beings but as resource channels seen through the lens of development in terms of construction materials, hydropower potential and agricultural utility.

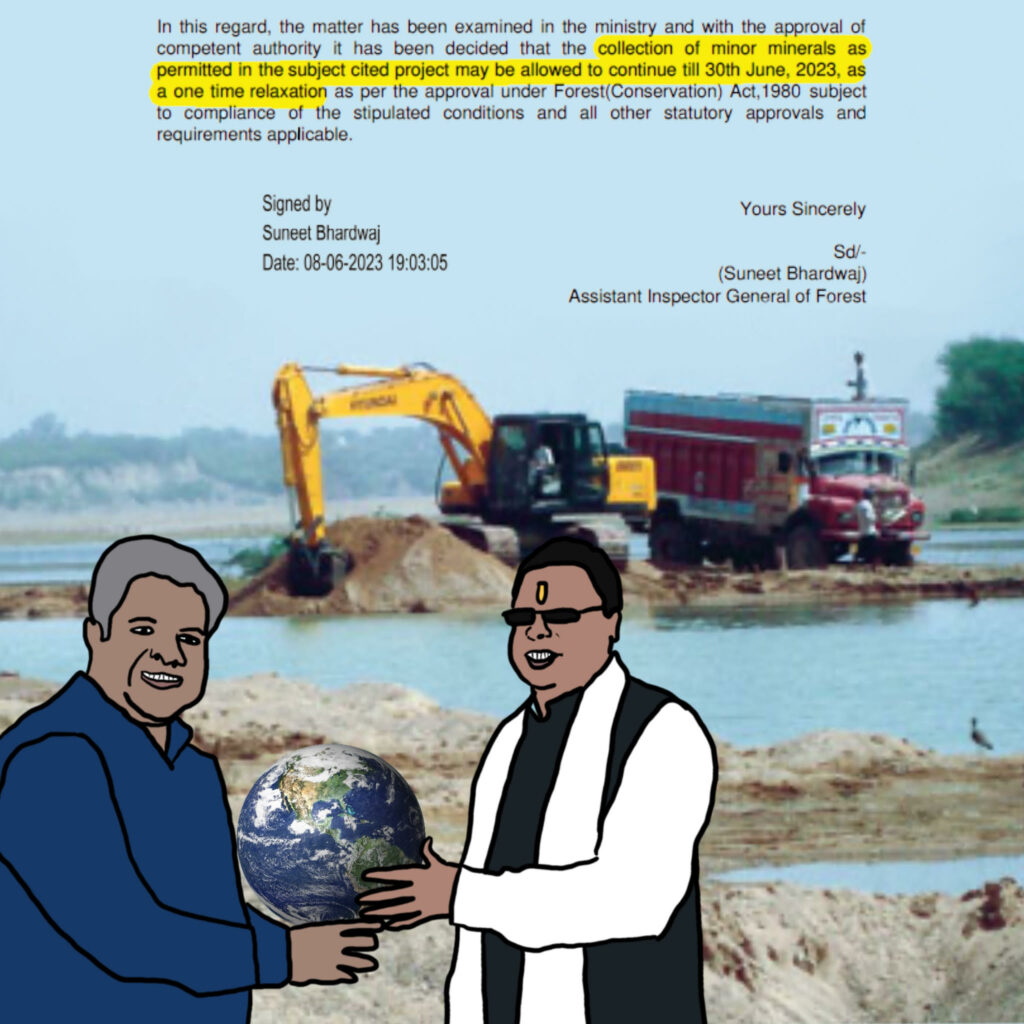

Figure 2: Two wolves in sheep’s clothing: In February 2023, Uttarakhand’s CM (right) lobbied the MoEFCC (left) for extended mining at the Gaula River. Despite non-compliance with prior environmental conditions, mining was permitted even during June—a monsoon month violating standard ecological norms. (Credit: Nirjesh)

Figure 2: Two wolves in sheep’s clothing: In February 2023, Uttarakhand’s CM (right) lobbied the MoEFCC (left) for extended mining at the Gaula River. Despite non-compliance with prior environmental conditions, mining was permitted even during June—a monsoon month violating standard ecological norms. (Credit: Nirjesh)

If all rivers were truly equal, then why do only a select few receive special legal or policy attention—while rivers like the Hindon or Gangan are left out?

Is it simply because they are not “big enough”? Or is it because certain rivers have been embedded in us through religious doctrines, turned into sacred symbols, while others are seen as expendable infrastructure—useful only for draining waste or feeding sand into our construction economy?

Rivers in our cities

Now, in cities, rivers are treated very differently. It’s not just roads that meander across the landscape — rivers still cut through our cities, quietly, persistently. Yet here, they are woven into our everyday lives in ways that render them invisible — reduced to conduits for household and industrial waste, remembered only during floods, droughts, or when their aesthetic appeal can be showcased. This selective attention is not accidental; it is shaped by systems that marginalize riverside communities and treat the river as infrastructure until a rupture demands notice.

If you live in or around Delhi, you might have heard of the Sahibi River, a lesser-known tributary of the Yamuna. The Sahibi River also known by another name: the Najafgarh drain. Most people today associate it not with a river, but with a sewage channel.

But this is not just a drain—it’s the course of the Sahibi River, with a total basin catchment area of 4,607.9 km². It forms part of an important ecological corridor that stretches from the Aravalli Hills in Rajasthan to the Yamuna River, supporting a chain of at least nine wetlands along its path.

Mentioned in an upper-caste text as the Drishadvati River, the Sahibi is also archaeologically important, with discoveries along its banks linked to the late Harappan phase of the Indus Valley civilisation.

The Sahibi River, entering Delhi from Haryana, once fed a vast 226 sq. km lake recorded in the 1883 Delhi Gazetteer. In 1865, colonial authorities began draining the lake by widening the river, initiating its transformation into the Najafgarh drain. Major floods in 1964 and 1977 led to further embankments and widening to control flooding in Delhi.

It seemed, over time, that no one wanted this watercourse—nor even the lake.

But the Sahibi doesn’t care. It has been existing—despite being widened, straightened, and amended. Through its seasonal flooding, it draws attention: from governments, real estate developers, and farmers alike. It asserts its presence, insists on being seen, and then moves on—passing quietly through Delhi until it finally meets the Yamuna.

And yes, that confluence is beautiful—not in any conventional sense, but in its own way. Polluted, dirty, perhaps unbearably stinking—yet alive. With vegetation, birds, insects, and people we often refuse to see as part of our city.

Figure 3: The confluence of Sahibi and Yamuna River. (Photo credit: Nirjesh)

Figure 3: The confluence of Sahibi and Yamuna River. (Photo credit: Nirjesh)

I never imagined that, behind the music blaring from the rooftop cafés of Majnu ka Tila, I would find majestic waterbirds in abundance, doing their watery things—completely indifferent to the city’s forgetfulness. Their presence felt like a sigh of silence in a city that rarely pauses, a reminder that life flows differently for those who are not bound by our rush. Perhaps the real issue is that we no longer consider urban rivers as rivers at all—we see them as drains, boundaries, or backdrops to development. But for the resident and migratory birds, the Yamuna is still a river, as alive and worthy as any in the wild.

Figure 4: Different waterbird species can be found around the confluence of the Sahibi and Yamuna — Little Egrets, Greater Egrets, Purple Swamphens, Painted Storks, and Grey Herons — a reminder that life still finds a way, even in extremities. (Photo credit: Nirjesh and Pragyan James Ali)

But beyond these romantic memories, and to return to the core of this reflection, we must ask again. Is every river just a river?

Conclusion:

In conclusion, whether roaring through mountain gorges or slipping quietly through floodplains, rivers share a universal role as sculptors, movers, and sustainers of life. Yet their treatment by human societies is far from equal. Some—like the Yamuna—are draped in religious symbolism, woven into the cultural and political fabric, and thus command protection, however imperfect. Others—like the Hindon or the Sahibi—are stripped of identity, renamed as drains, reduced to utility channels, or simply ignored in public memory. The difference lies less in their ecological value than in the narratives we choose to attach to them.

Across histories, mythologies, and geographies, this selective reverence creates a hierarchy of rivers, where cultural significance can eclipse ecological reality. In urban settings, this inequality becomes sharper: rivers are altered, channelled, and sometimes erased altogether, even as they continue to host life for birds, insects, and communities we often overlook.

If there is a common thread, it is that all rivers—celebrated or forgotten—remain active agents, shaping land and sustaining ecosystems, whether or not we acknowledge them. The difference is in our gaze: we have learned to love some rivers as sacred beings and tolerate others as waste conduits. This divide is neither natural nor inevitable.

To truly live with rivers, we must extend our respect and care beyond the few that dominate our imagination, recognising that every river, regardless of fame or filth, is part of the same interconnected pulse of the earth.

Notes:

- Leong GC. Certificate Physical and Human Geography. Oxford University Press; 2019.

- In a geographical sense effect of running water are given more prominence than the precise definition of a river. Water can run anywhere where there is an elevation gradient. In that light it is more meaningful to equally value the gradient than to fixate on where the river begins or ends. River perhaps is a social construct shaped by culture, sentiments and administrative boundaries. But ecologically it makes more sense to focus on running water and its capacity to connect landscape and sustain life. To rejuvenating our rivers, we must begin by changing our perception. We need to stop valuing only the sacred or the spectacular and turn our attention to the elevation gradient and just running water.

This article is a reworked adaptation of a blog post originally published on Youth Ki Awaaz, which can be accessed here.

Author by – Nirjesh Gautam, is a researcher at the Centre for Urban Ecology and Sustainability, Ambedkar University Delhi. He explores the diverse forms of urban nature through an interdisciplinary lens, focusing on the relationships between people, cities, and non-human life.