Introduction

The Sahibi river originates in the Aravalli hills in Rajasthan, beginning its journey from the Pithampur and Bari Jodi region and winding through Jaipur, Alwar, and Gurgaon in Haryana before crossing into the National Capital Territory of Delhi via the Dhansa border. Once it enters Delhi, the river is more commonly referred to as the Najafgarh drain, a name that reflects its present state more than its historical identity. Eventually, the Sahibi merges with the Yamuna River at Wazirabad, and from there, its waters make their way into the Ganga at Allahabad.

Scientifically classified as an ephemeral river, the Sahibi flows only during certain months, usually in the monsoon season, remaining dry for the rest of the year. Sahibi River covers around 10,000 kilometers, and its total length from origin to confluence is around 317 kilometers. Over the decades, the river has become an example of how urban expansion, infrastructural interventions, and bureaucratic oversight can drive a natural water body toward extinction.

Historically, during the 1960s and earlier, the Sahibi flowed freely into Delhi, discharging its waters into the Najafgarh Jheel (lake). This natural course often led to the submergence of adjacent lands during the monsoons. To mitigate the seasonal flooding, the river was gradually engineered into a stormwater drain. However, this transformation did not stop at flood control. With Delhi’s rapid urbanisation and lack of systematic waste management, the canal that once carried monsoon waters was increasingly burdened with untreated sewage and industrial effluents.

Over time, this converted the once-vibrant river into what is now known as the Najafgarh drain, its name, status, and function all irrevocably altered. Scholar Ritu Rao, in her work, traces this transformation and argues that the making of a drain is not an isolated engineering decision but a long, cumulative historical process intricately linked to urbanisation.

Nullahs or naalas, originally meant to carry only stormwater, became the unintended conduits for urban sewage. As residential colonies, factories, and other infrastructure mushroomed across the region, waste from homes and industries found its way into these nullahs. Few people today are aware that rooftop rainwater and domestic wastewater are supposed to be channeled through entirely different systems. The conflation of these systems reflects a deeper failure of urban planning and environmental governance, where nature’s pathways are forcibly overwritten by the infrastructure of a growing city.

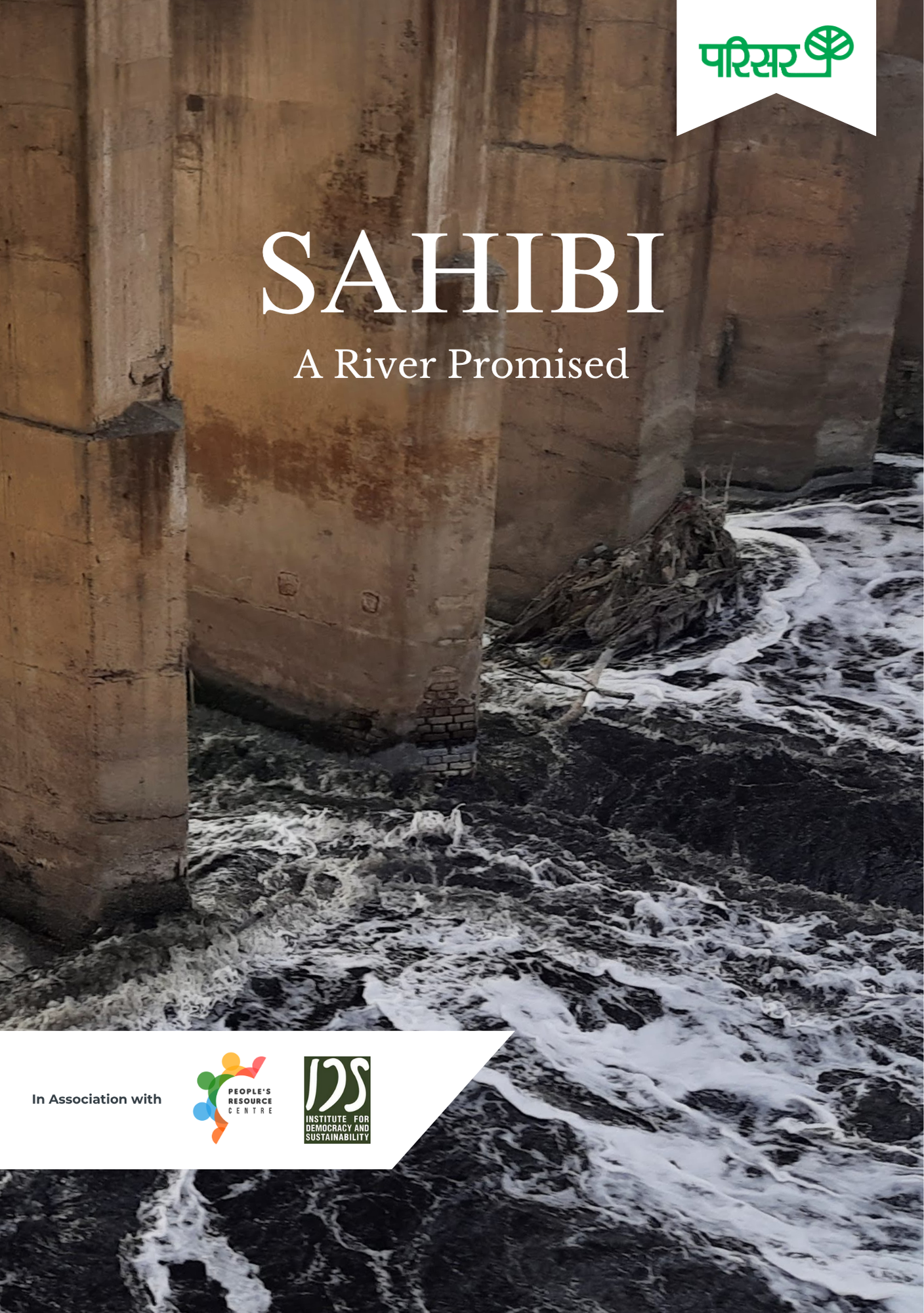

This rechanneling of the Sahibi’s water, combined with structural interventions like the construction of the Masani Barrage, brought the river’s natural flow to a near standstill. In the mid-1990s, the last significant flow of the Sahibi was recorded, and since then, its waters have largely been replaced by effluent and garbage. What remains is not a river in any ecological sense, but a contaminated conduit, symbolic of broader failures in environmental stewardship.

This situation is not unique to the Sahibi. The Yamuna river, into which the Sahibi empties, has also been declared biologically dead, a river that no longer supports aquatic life due to high levels of pollution. Despite repeated budget allocations and grand promises made during every election cycle by successive governments for the Yamuna’s “rejuvenation,” we see no change in the looks and shape of the river. Often, these efforts resemble cosmetic beautification projects more than genuine ecological restoration.

To understand the failure of Yamuna restoration, we must interrogate its sources of pollution, of which the Sahibi is a major contributor. Without addressing tributaries like the Sahibi, any attempt to revive the Yamuna is bound to be superficial. A truly holistic restoration plan must incorporate upstream interventions and tackle the interlinked ecology of the river system.

In recent years, the term “Sahibi River” has begun to resurface in policy documents, court orders, and even on platforms like Google Maps, where its name was recently updated. While many residents still refer to it as the Najafgarh Naala, or more vaguely, as an “unnamed drain”, this linguistic shift is indicative of a growing recognition of the river’s lost identity. Since 2022, various government departments have shown renewed interest in its restoration. An initial proposal to revive a 12-kilometer stretch has now expanded to cover the entire 57 kilometers of the river within Delhi. The office of the Lieutenant Governor has emerged as a key proponent of these efforts.

The Delhi Irrigation and Flood Control Department has been tasked with desilting the riverbed and restoring embankments, while the Delhi Jal Board is responsible for intercepting and treating the sewage that flows into the drain. While these efforts are underway, one might ask how can a river with no flow and only sewage water be restored? Does a river even exist outside the promise of its restoration? Will Sahibi be able to make it out of the court orders, twitter posts, governmental papers, and google maps and make it into its original course?

These questions point to a deeper problem with environmental restoration in India. Projects are often “underway” indefinitely, rarely resulting in substantive change. In the case of the Yamuna, we have seen decades of media spectacles, political blame games, and recycled promises. Experts and scientists have repeatedly offered actionable strategies, yet little has translated into on-ground impact. Words, policy statements, media reports, political speeches, have become saturated with repetition. They no longer hold the power to illuminate or mobilise.

In moments like these, when language itself feels inadequate, we turn to alternate modes of understanding. This is where visual ethnography becomes a powerful tool. In this study, I use the medium of images and field documentation to capture and communicate the current state of the Sahibi, a river that no longer exists. Through photographs and visual narratives, I attempt to piece together a portrait of this fragmented river system, one that has been erased by urbanisation, remembered in name alone, and trapped between the idea of restoration and the reality of disappearance.

I undertook a journey along the course of the river, employing the method of visual ethnography as a key tool to investigate and document the complex relationship between the river and the communities that live alongside it. Through this immersive approach, we were able to uncover the many ways in which this historically intimate connection has been fractured, most notably through layers of mediation imposed by state authorities, as well as through a persistent pattern of neglect that has unfolded over time. This report aims to present a comprehensive overview of the current state of restoration efforts that have been initiated along various segments of the river. In doing so, we also examine the broader ecological landscape that surrounds the river, an environment that not only depends on the river’s health but also actively sustains its natural and human systems.

To build a nuanced and multifaceted understanding of the river’s present condition, we engaged in conversations with a wide range of stakeholders. These include on-ground staff members working at different restoration sites, environmental experts with domain knowledge, caretakers responsible for maintaining restored embankments, long-term residents who have witnessed the river’s changes firsthand, and the principal petitioner in the ongoing National Green Tribunal (NGT) case concerning the Sahibi river. Their testimonies, perspectives, and lived experiences collectively help us construct a more complete and grounded portrait of the river’s evolving status. What is the relationship of people with its commons? Who are the occupants of a river bank that runs with sewage? Who all are dependent on this water and its ecosystem? What does it say about the vulnerability of these groups? How is a city made possible by engendering vulnerabilities for some communities and people? What is the way ahead? are some questions that this visual ethnography shall attempt to address.

Author: Krishanu

Photographs by: Krishanu & Rajendra Ravi

Coordinator: Rajendra Ravi

Fieldwork support: Nanhu Prasad

Designer: Sanjana Gupta